The quarantine convert: Balancing public health and human rights, Published in the Daily Maverick, 14 December 2021

My public health brain approaches Omicron with an abundance of caution. What matters is not where it came from, but where it is going, and how to stop it in its tracks. As smart scientists race to find out more, smart policymakers need to act cautiously and well.

Ten days ago an Asian global health colleague sent our group chat a message, saying he was being sent home early from his mission to southern Africa. He would be in a government quarantine facility so might be hard to reach. He wasn’t complaining, or suggesting it was the wrong thing. He wasn’t looking forward to the food though!

An hour before his message pinged in, I’d pressed send on an article I’d written for Maverick Citizen raging about why the UK slapping travel restrictions on a random bunch of countries is rotten public health. So you might be surprised that I was really glad to hear that he was going into quarantine.

I’m a Brit, but for the past month I’ve been living in Asia. It’s a massive relief – not only because I’m spared the day-to-day horrors of life under a toxic, corrupt government, but also because my risks of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 are much lower.

I feel a lot safer here.

Soon after the group chat message, my Facebook notifications started to jump. The same day the Indonesian government announced that quarantine would be extended to 10 days; members of the “Visa & Immigration group” were going wild with questions and complaints.

It was two weeks since my (double-vaxxed) son and I had landed in the country, heading straight into three days in quarantine.

During our time – blitzing on Netflix and sleeping off jet lag – we heard that quarantine would soon reduce to one day. It sounded like an obvious plan to revive Bali’s desperate tourism economy just before Christmas, but they never made it down to the quick overnighter. Soon after we were released, it crept back up to seven nights and on 3 December the Indonesian government insisted on at least 10 days’ quarantine for all.

Facebook group members were outraged, squealing about the unfairness and expense of it all (it’s free for residents, not for visitors like us). Of course, the frustration with expense is understandable. At the same time, their tourism economy has tanked and they really need us to share our wealth (which is why I didn’t kick up a fuss when our local hotel charged us the same for three nights as they’d quoted previously for five – which would have been the protocol if we’d landed a week earlier).

By contrast, a recent Daily Maverick article reports that big international hotel chains in the UK have been transformed into “UK government approved” quarantine facilities and are hiking prices to outrageous levels, forcing travellers into flea-ridden dumps serving revolting cold food.

Most of the rants on the Indonesian group were no longer about poor food (the trending topic before), but rather from travellers perplexed that holiday plans were being ruined. The best riposte came from a long-term resident, who has married into a local family:

“If you are not willing to do the quarantine requested by the Indonesian government to protect the people of Indonesia: maybe it will be a much better idea not to plan to come to Indonesia.”

The frustration of these furious wannabe tourists who don’t want to test, pause and test again before they come on holiday – or to be reunited with much-loved family members (our reason for being here) is understandable. Still – and I feel rather queasy admitting it – quarantine makes sense to me.

Quarantine, public health and human rights

Stay with me.

I’m not talking about the UK’s rank profiteering, bouncing off the back of unjustifiable travel restrictions against a bunch of SADC countries – action that reeks of economic sanctions, racism and political game playing.

Rather, I’m talking about smart public health.

There’s a logic to separating all people on arrival rather than singling out a set of countries and banning them from departing – at least for a short time.

The World Health Organization seems to think so, too.

In an advisory on international travel issued on 30 November, it criticised the countries that have isolated southern Africa, yet warning (bluntly put): “This isn’t a great time to travel, so if it’s not essential, stay home. And if you must travel: test repeatedly and quarantine.”

Or in more precise terms:

“National authorities in countries of departure, transit and arrival may apply a multilayered risk mitigation approach to potentially delay and/or reduce the exportation or importation of the new variant. Such measures may include screening of passengers prior to travelling and/or upon arrival, including via the use of SARS-CoV-2 testing or the application of quarantine to international travellers.”

At the word “quarantine” my human rights defence mechanisms knee-jerk into action. Alert to anything that smells of forced incarceration, especially of the poor or vulnerable, memories flood in of Cuba, late 1980s, locking up people with HIV. A decade later, when effective AIDS treatment came on stream and Cuba ended its HIV quarantine policies, I remember sitting with a bunch of fierce, and fiercely bright, treatment activists mulling over whether Cuba had got it right. Numerically they had. By then the pandemic was racing through Africa but still Cuba had fewer than 2,000 cases.

But the human rights abuses, the deepening of stigma and hatred, the loss of liberty by people from the most marginalised communities, far out-balanced the apparent “success”. And even if the number of infections was the only thing that mattered, who’s to say that if Cuba had invested more than$0.5-billion in brilliant behavioural public health interventions instead of quarantine they would not have achieved the same low caseload?

Covid-19 has many lessons to learn from HIV. But Cuba’s quarantine story is not one of them. After all, SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted in very different ways, usually in public spaces, and mostly in very different communities.

And that is what led me to question my knee-jerk reaction to quarantine. That, and flying from the UK to Italy last month, my first time on a plane since I left South Africa on 3 March 2020.

The Italian job

Italy’s (not quite fast enough) response to Covid in early 2020 drew on centuries of public health knowledge. Ever since the 14th century, when Venetians sent locals sick with the bubonic plague to the island of Lazzaretto Vecchio for quaranta giorni (40 days), quarantine has been a smart part of the public health armoury. Social mixing has always brought the threat of disease transmission, and busy trading hubs like Venice created the perfect opportunity for the plague to flourish.

If you’ve ever visited this exquisite lagoon city, you’ll know that personal space and sanitation are never givens, even with 20th-century innovations. Just last month I dipped back for a mini trip and was reminded of how impossible it is to keep 2m from anyone on the glorious calle that thread through the city, tying the canals together.

Separating those seemingly sick with the plague to be treated at a hospital on a distant island made perfect sense 500 years ago. And it was equally logical to build another hospital on a different island, Lazzaretto Nuovo, for incoming boats that may have sick passengers.

“This was the only way to protect everyone’s health and allow the economy to continue,” says Venetian researcher Francesca Malagnini (Cited in Venice’s Black death and The Dawn of Quarantine, Sara Toth Stub, Discover Magazine, 27 April 2020).

Don’t get me wrong. Quarantine alone is never the answer – the early version had many problems: diagnostics didn’t exist, creating a painful conflation of treating those who were clearly sick, with waiting to see if the rest developed symptoms. Naturally, many who arrived healthy succumbed while on Lazzaretto Nuovo, picking up infections from others on the boats. Still, sweating it out for 40 days to see what happens wasn’t a bad algorithm at a time when no one could turn to peer-reviewed papers to work out the modes of transmission and natural history of disease.

And it wasn’t a crude “wait and see”. Built into the quarantine model was a hospital facility with the expectation of caring for the sick and dying. They weren’t shoving people onto these pretty islands for the fun of it or to rip them off, rather to keep trade flowing – safely.

Fast forward to now

The UK government encouraged a blast of tourist travel in mid-2020, with people incentivised to hop on highly subsidised flights (often as little as £10 a pop). Predictably the push to boost the UK economy led to a new spike in Covid cases and by November 2020 the UK was back in hard lockdown.

In 2020, I’d been too sick to even travel across London, but, feeling better and double-vaxxed, I felt quietly confident about the test-and-travel routine. My mini trip to Italy required that I show my double vaccinated status and pay for two lateral flow tests, 48 hours either side of a short trip (post-Omicron they’ve tightened things up).

The £108 I paid for those tests felt like a bribe. The tests were performative not diagnostic – my results bounced back five minutes after some untrained shop clerk, wearing their mask like a chin guard, rubbed a Q-tip around the bottom of my nose.

“UK government approved” travel testing clinics have sprung up all over the country, backed no doubt by the same Tory investors rubbing their hands with glee at how well their PPE businesses are doing (I wonder how much they are investing in these nasty Red List hotels?). Without vaccination and a negative test result, Italy would have sent me immediately into five days of self-isolation on arrival, followed by a much more pricey (and reliable) PCR.

On return, I was allowed to wander back to Britain without pre-departure testing and just rock up at the Q-tip clinic two days later to get my (inevitably) Covid-negative result; it arrived before I’d ordered my coffee at the café over the road.

Now that I am in Asia, I feel much safer. To get here, I paid a hefty fee – nearly £1,000 for two of us to deal with the various Covid protocols. We flew through Hong Kong, taking (proper) PCR tests 48 hours before the plane, enjoying a flight with more cabin attendants than passengers. We navigated through hours of bureaucracy and separate channels in transit, all shops were closed at Hong Kong airport and about half of the tiny number of other passengers were wearing disposable white suits covering their own clothes.

On landing in Jakarta we had a PCR test before picking up our luggage, and were whisked off to a quarantine hotel as soon as our (second in 52 hours) PCR negative tests came through. The surreal bit – at 2am – was handing over our passports in exchange for a baby-pink wristband, before we were locked into our “suite” on the secure ninth floor of the hotel.

The food wasn’t great, but we were grateful for the competing muezzins under our window when, at 4am on day three, our cheerful hosts escorted us back downstairs, handing us over to the local laboratory. This time – just like our airport experience – trained healthcare workers, resplendent in white hazmat suits and perfect PPE, did their worst, scraping the backs of our throats and sticking the swabs high up our nostrils. Ten hours later we were free to leave. I’m not surprised that one of the first B.1.1.519/Omicron cases was found in Hong Kong quarantine. They know what they are doing in Asia.

I confess that since being here, I’ve been less diligent with mask wearing in public spaces than in the past two years in infested Britain. We’re mostly outside, very well ventilated, and I pop it on in the shops, cafés and local Ubers where staff all wear masks. Many proclaim “all our staff are vaccinated”, and many quite proudly show off their certificates; drivers have to keep them to hand as police do spot checks.

South East Asia sets an example

The main reason I’m slacker is that I know how rigorous the process is for the few of us who can get into the country; and I know the numbers. Over the past two weeks Indonesia – the world’s third-most populous nation with more than 273 million people – reported 3,897 cases, averaging 236 new cases per day and 10 deaths (Johns Hopkins University, Covid-19 data repository, data for 8 December). Brighton, my seaside home in the UK – which has a population of 670,000 – today reports 6,775 active cases of Covid, with more than 1.1 million cases in the UK and close to 200 deaths a day.

And it’s not just the epidemiology – in recent weeks my UK friends have unrelenting stories of local outbreaks at school (and not being allowed to keep their own children home) and whole families struggling with reinfection. In Bali we’re worrying about dengue. Friends have it and my driver told me how concerned everyone is in his village. Covid? Yes, he did three weeks’ isolation when his neighbour got sick. That was more than a year ago. He hasn’t heard of a case since

It’s really not surprising that Indonesia is doing so well. Asia has an impressive record on this stuff. Ever since SARS-CoV-2 emerged in early 2020, Asian countries have been ahead of the curve. They’ve tackled other coronaviruses in the past and kept them at bay.

If you’ve travelled in Asia before the pandemic you’ll know that mask wearing is a thing. Respect is central to Asian cultures; the local version of ubuntu means popping on a mask if you have a hint of a sniffle, or have been near someone who has. The newsreaders, broadcasting from separate studios, appear on TV wearing N95 masks.

It’s expats who are lax with mask wearing (I put my hand up); and it’s also only the expats complaining about the quarantine. Local Indonesians have to quarantine, too.

The thing is that it works – because it applies to everyone, not to a random set of countries on some spurious “Red List”.

A hop over the sea in Malaysia, a 19-year old student returning from a home visit tested positive for Omicron. The case has been handled with impressive calm. She was in quarantine by the time the result came through and all of her contacts (at the transit airport, bus drivers to the quarantine facility, etc) have tested negative. She was released from quarantine when she was better and so far that’s it.

One of the things that is important about the quarantine model is that it should be about testing as a pathway to care; not testing to keep people out. That’s part of why the only case in Malaysia was handled well – and they have impressive lab facilities, too.

Of course it is hard that families can’t fly out for a quick Christmas break, and it is awful for Bali’s flailing tourist industry, but keeping the influx of visitors down (no more than 6,000 a day – probably fewer now as quarantine hotels are at capacity) there is a chance that they will keep the Covid numbers low if this variant really is super-infectious. The Indonesian see-saw approach to quarantine stands them in good stead – it buys the country time for researchers to find out what’s really going on with Omicron.

Balancing risks

Good public health is all about balancing risk; we do this with other screening programmes. Most people with SARS-CoV-2 will test PCR positive within five days of infection, but in some cases the incubation period is 14 days.

Indonesia’s three-day protocol was only for vaccinated people so it made sense to hazard a bet that most of us would not be infected and if we were we would show up positive within five days (the time it takes to get through the three pre-departure, on arrival and leaving quarantine PCRs). Now that we have an unknown, potentially super-infectious variant on the block that may excel at reinfection, it makes sense to lean towards the super-cautious and extend the duration.

At least for a while. Quarantine is not a forever thing.

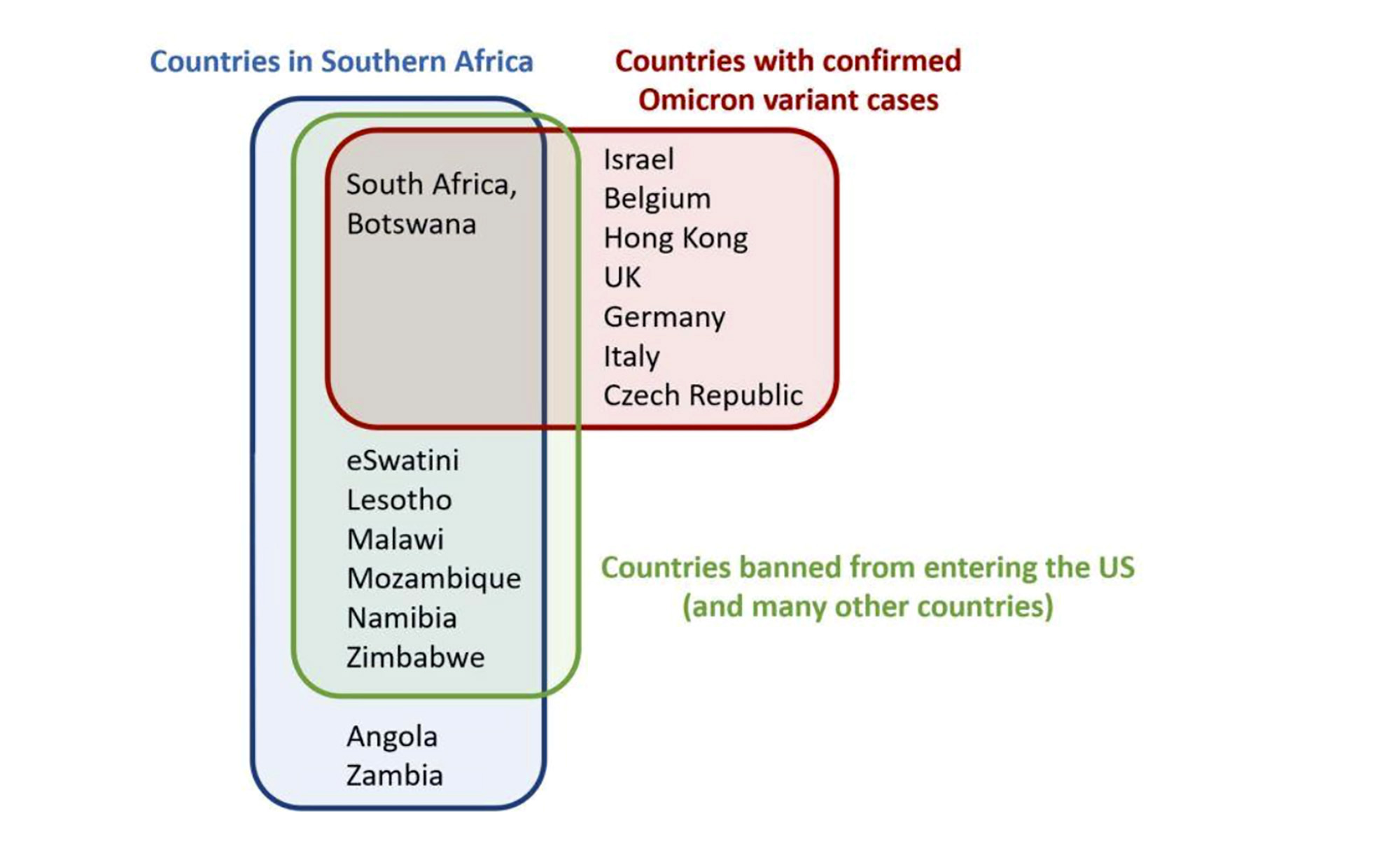

What is not smart is restrictions linked to facile assumptions about origins. When 10 African countries were shoved on most travel ban lists, only two of those countries had confirmed Omicron cases. At that point there were nine countries with confirmed Omicron – only two of them were on the travel ban lists. Yup, the African ones. No one in the vaccine-rich, “boosters for all” part of the world took the hit. Slam down the barricades – and try to forget that we rich and selfish ones are already swirling in our own stew of infection.

Singling out a cluster of countries makes for great headlines – and rubbish public health. Unsurprisingly, as knowledge grows – and at a remarkable pace – we find out that maybe things are not as simple as they seem. We now know that at least two cases of Omicron were found in Europe (the Netherlands on 19 and 23 November) before South Africa rang the alarm bell on 24 November. And the Israeli doctor sick with it is certain he picked it up at a busy, semi-masked conference in London 10 days earlier; he arrived there on 19 November. Maybe this is another European export after all?

And so what?

On one level, the origin story really couldn’t interest me less. It throws me back to the early days of the other pandemic. In the Eighties I was the AIDS bore. At dinner parties, with friends whose lives were heading in very different directions, I would rock up armed with a bottle of red and answers to the two most common questions: Where does AIDS come from? Is oral sex safe? I could only answer one, and it was the only one that mattered: “It’s probably fine; enjoy yourselves” and “Who cares where it came from.”

My public health brain approaches Omicron with an abundance of caution. What matters is not where it came from, but where it is going, and how to stop it in its tracks. As smart scientists race to find out more, smart policymakers need to act cautiously and well.

And my colleague?

He’s just out, tested negative repeatedly and his Japanese meals looked a lot tastier than my Indonesian ones (shame about the plastic trays though). He’s looking forward to getting back to southern Africa soon. Me too, and I’ll be happy to spend a few days in quarantine, just in case I bring something nasty with me from London.